Article from Press Tribune

Barbara Erysian has lived with the story since before she was 10 years old.

Barbara Erysian has lived with the story since before she was 10 years old.

She doesn’t remember the first time she heard it, but the details — a man buried alive, children orphaned and starving, a global migration to escape the extermination of 1.5 million fellow Armenians — never left her.

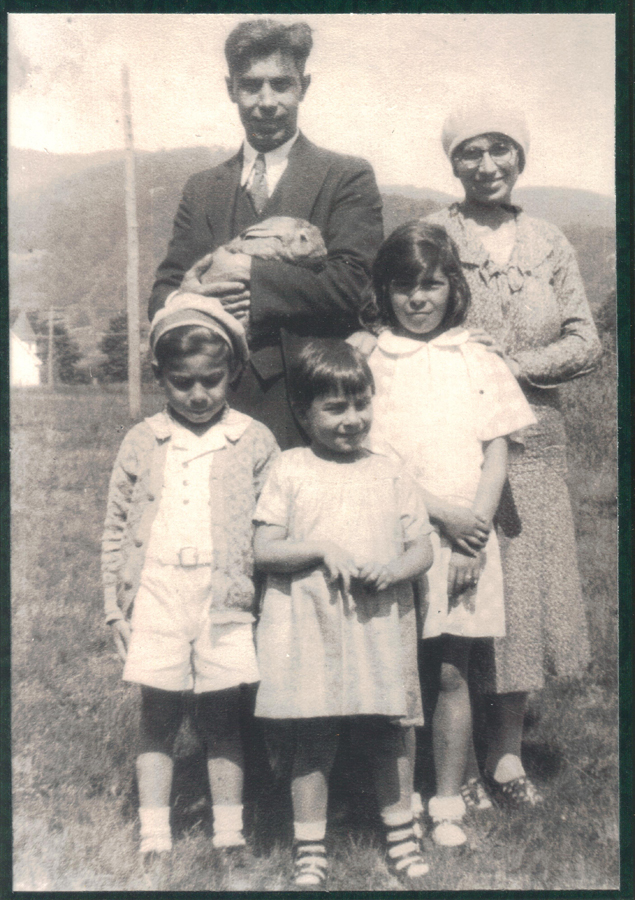

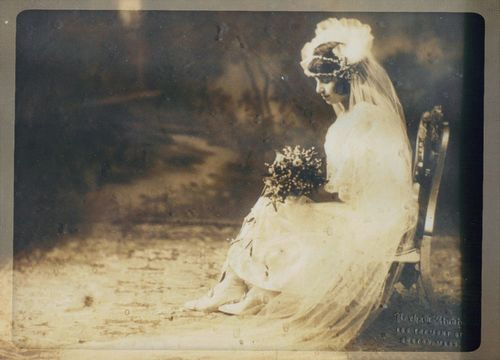

Erysian, a Granite Bay resident, heard the story from her grandmother Alice Zerahian many times growing up. It was autobiographical, and always ended with a plea: “Tell your children. Tell your children’s children. Never forget.”

Now 55, Erysian knows she is descended from a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, in which the Ottoman Empire targeted a religious minority for annihilation by executions, death marches and other brutal tactics between 1914 and 1923. Taking her grandmother’s plea to heart, she has launched into a years-long process of turning Alice Zerahian’s story into a movie.

Old terror, new headlines

Alice Zerahian immigrated from Armenia to Massachusetts in the early 1920s and then moved to Fresno, where Erysian remembers spending time with her on holidays and week-long summer visits. As a math professor at Sierra College since 2004, Erysian hadn’t had much occasion to revisit her grandmother’s story until she saw TV reports of ISIS activity in 2013, and it stirred something in her memory.

“I felt that people should know somehow, and understand, this persecution is not a new thing — that this has been going on in that region for a very long time,” she said. “As a child I did not even understand what (my grandmother) was telling me, but she would tell me the story repeatedly, and it laid on my heart. Four years ago, I just realized that (sharing it) was something I needed to do.”

“I felt that people should know somehow, and understand, this persecution is not a new thing — that this has been going on in that region for a very long time,” she said. “As a child I did not even understand what (my grandmother) was telling me, but she would tell me the story repeatedly, and it laid on my heart. Four years ago, I just realized that (sharing it) was something I needed to do.”

Hoping to reach the widest possible audience and being skeptical that a book would do it, she set about writing a screenplay. Erysian had never attempted such a thing before, so she started researching in earnest — not only history, but screenwriting and storytelling.

Around her grandmother’s story she had to populate an entire world of missionaries, supporting characters, soldiers and antagonists with their own backgrounds and struggles. The act of creation was a challenge, fulfilling the dramatic needs of a screenplay without compromising the reality of the story that inspired her in the first place. She also wanted to respect why the story resonates without leaning too hard on timeliness.

“There’s a lot of animosity still between the Turkish people and the Armenians, because to this day the Turkish government denies that there was a genocide,” she said. “It was important to me through this process to not make it political — to genuinely make it just her story.”

“There’s a lot of animosity still between the Turkish people and the Armenians, because to this day the Turkish government denies that there was a genocide,” she said. “It was important to me through this process to not make it political — to genuinely make it just her story.”

The pitch

Every summer, writers descend on The Great American PitchFest in Los Angeles to woo producers and investors with their dream projects. It was there that Barbara Erysian saw her window. Having spent the better part of two years on writing and research, she flew to Los Angeles in 2015 with a completed draft.

The title was simple: “Who Will Remember.” The pitch was quick, by necessity, limited to about five minutes. The audience each time was tired, having listened to who-knows-how-many love stories and pipe dreams that day. But where seven producers passed, an eighth, Max Freedman, had a vision.

“I work intuitively, so I was struck positively about it. I heard probably 50 or 60 five-minute pitches that day,” Freedman said. “I saw Barbara approach my table with her grandmother behind her, which was impossible since her grandmother had long ago deceased, but I could visualize her grandmother … (Barbara) just said really clearly to me what the story was, and I instantly got it. It just clicked. For whatever reason, it was somewhat magical, I think.”

More than just a producer, Freedman, 73, is a Los Angeles-based filmmaker who makes his own movies through MFM Productions, the producing arm of his filmmaking and publishing company. Instantly sold by Erysian’s pitch in 2015, he spent most of the ensuing two and a half years refining Erysian’s original script.

“The first thing I did was read the script, and I was amazed that someone who teaches math for a profession for 30 years could achieve such poignancy the first time out,” he said.

“The first thing I did was read the script, and I was amazed that someone who teaches math for a profession for 30 years could achieve such poignancy the first time out,” he said.

Eventually the script scored a rare “recommend” rating from Slated, a professional script-analysis company, as opposed to “consider” or “pass.”

The next step was to budget and raise money for the project. As with most films, that’s where “Who Will Remember” hit its first snag, so Erysian suggested making a short film — a proof-of-concept to persuade investors to pay for a feature. Freedman and Erysian had budgeted the feature version at $14 million, but a 15-minute short they could finance themselves for about $13,000.

Write global, shoot local

To assemble the crew Max Freedman tapped Stephen Chollet, a two-time Emmy Award-winning video producer in Chico who then recruited most of the talent behind the camera.

Chollet has done a little of everything, from independent films and shorts to documentaries, commercials and corporate videos. But besides being an opportunity for work, he said, the project intrigued him. It was a learning exercise, as he didn’t know much about the history of the Armenian Genocide, and he liked that it was a dramatic short film with a documentary quality to it, like recreating history.

Chollet has done a little of everything, from independent films and shorts to documentaries, commercials and corporate videos. But besides being an opportunity for work, he said, the project intrigued him. It was a learning exercise, as he didn’t know much about the history of the Armenian Genocide, and he liked that it was a dramatic short film with a documentary quality to it, like recreating history.

“It’s a true family story, and we’re bringing that to life,” he said. “(It’s about) bringing some awareness to that — as the name of the film says, ‘Who Will Remember.’ I think it’s an important project.”

Unable to shoot across the globe due to budget constraints, Freedman, Chollet and their crew found what they needed in and around Erysian’s home in Granite Bay. They recruited actors from Los Angeles, the Bay Area and Merced, shooting nine scenes in two days at three locations in January 2018: in Erysian’s house, at Folsom State Park (the north shore can pass for a desert, as Erysian pointed out), and on an impromptu set in La Belle Vie in Old Town Roseville.

They also consulted Armenian members of His House Ministries Armenian Church in Rancho Cordova to be sure the costumes, props and other details were accurate. The church gave a blessing for the project on Jan. 7, and members were present for some of the filming. Lusine Aleksanyan, a member of the church whose first experience on a film set was watching the reenactment of a murder, found it eye-opening.

“It’s a lot of fun, but sad to watch at the same time, because it really happened,” she said. “I feel like more people need to know what really happened back then … how many people got killed, how women were treated, the kids, the men.”

Lessons from history

One of the ironies of Alice Zerahian’s story is that she lived into her 90s, got Alzheimer’s disease and forgot everything in the end. But she survived the genocide to tell the tale, and her granddaughter has spent much of the past four years contemplating why it’s so important to remember.

“This movie is told from the perspective of a young girl and her little brother who survived, and I keep asking myself two questions: one is, why did she survive, or how did she survive that genocide … and why me?” she said. “Why do I feel so compelled … to tell this story?”

A diminutive figure at 5’1”, perhaps Erysian relates to her grandmother in that respect. At least she marvels at the girl’s mettle in surviving what millions of others did not. But Erysian never really found the answer to “why me,” save a few spiritual insights that amounted to, “It doesn’t really matter.” Though she’s not a screenwriter, or “Hollywood,” or even fluent in Armenian, she believes an important story was handed to her by her grandmother, and she’s doing something with it.

She hopes to see the short film completed by April 24, in time for a premiere at the Capital Christian Center’s commemoration of the genocide.

“When 1.5 million people are killed for the reason (of) their particular culture, religion or ethnicity, and killed in violent and barbaric ways, I don’t think that it’s good as a human race for us to ignore those events or deny that they happened,” Erysian said. “I think people should know about those events, so we can learn from them.”